Greetings at the beginning of the fall term. Days and evenings grow cooler, sunlight softer. Soon leaves will turn color and fall lazily to the ground. The rainy season with our Portland drizzle, cooling breeze, and gentle melancholy is on the horizon. The rhythm of the school year kicks in. A time of renewal. My spirit refreshed, I get back to the stuff of my life with reading, study, and maybe some poetry projects for the weeks and months ahead.

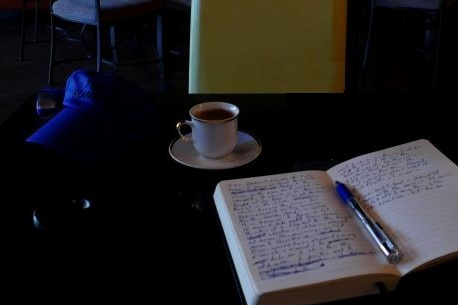

Traditionally I do not get much done during the summer months, the time of vacation on the school calendar. The summer just past was an exception. Affairs of the day prompted a steady stream, almost a gushing torrent by my standards, of agitated commentary and analysis laced with I hope not too much invective and vitriol. Accounts of a June excursion to Tulsa for the Tulsa Runner twentieth anniverary celebration, reflections on This Writing Life, and a renewed encounter with Gregory Corso and the Belief in Poetry provided a welcome break from the polemics. Not much joy at the poetry desk, where the muse kept her distance. One poem from last month may be a keeper, and it is possible that scattered lines and passages in the notebooks may yet come to something.

What do I have in mind when I speak of reading and study projects for the fall term? A few years ago I found a selection of free online courses at Open Culture (a nice resource for free cultural and educational media on the web). I studied the Greeks with Ancient Greek History, a Yale course, accompanied by selected reading, Homer’s Iliad, Aristotle, Herodotus, H.D.F. Kitto’s The Greeks, etc. A couple of years later I went in for a little English history with another Yale course, Early Modern England: Politics, Religion, and Society under the Tudors and Stuarts and Lord Macauley’s The History of England. In between those two I took a shallow dive into Marx on my own with The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, The German Ideology: Part I, sundry short tracts and excerpts, and a biography by Jonathan Sperber, topped off with a rereading of Eric Hobsbawm’s Europe: Mother of Revolutions. Yes, these are things I do for fun. Maybe I should get a life.

I have not settled on a subject for this fall. First I must finish off Harold Bloom’s Genius (2002), an 800-page appreciation of one hundred writers of literary genius that has occupied a considerable chunk of my summer. Bloom is not for everyone. He has long been a fierce adversary of “academic imposters who call themselves ‘cultural critics.’ They are nothing of the sort: they are resentment-pipers,” what he refers to elsewhere as the School of Resentment. The disregard is mutual.

Genius is liberally sprinkled with passing remarks bemoaning the decline of our institutions of higher education. His particular concerns are the teaching of literature and literary criticism where he is engaged. Bloom looks to Samuel Johnson, to his mind still the greatest of all literary critics, as an exemplar: “The Johnsonian inventiveness, for me, defines what literary criticism ought to be and very rarely is: the appreciation of originality and the rejection of the merely fashionable.” Bloom’s advocacy for the idea of literary genius and greatness, and defense of the literary canon that went with it, are out of fashion in our time of single-minded leveling when assertions of distinction, that some writers and works are of greater value than others, are liable to meet with damning charges of elitism.

To be fair, Bloom can be arrogant and full of himself, given to sweeping claims and pronouncements from on high that are beyond my capacity to fathom or otherwise have me shaking my head. These faults are more than compensated by an infectious love for reading and literature that comes through in almost everything he wrote. Bloom seems to have read everything, and remembered most of it. In the chapter on Iris Murdoch he begins, “An incessant reader and insomniac, I still have failed to reread all twenty-six of the late Iris Murdoch’s novels before writing these pages.” Reread, mind you.

I could do worse than devote the term to reading and rereading writers Bloom discusses, not least dead, white women I should have read somewhere along the way but somehow missed: George Eliot, Willa Cather, Edith Wharton, Iris Murdoch, for example. I recall plowing through Silas Marner in high school and finding it a joyless chore. Maybe a second time around would be similar to my experience reading A Tale of Two Cities in my thirties, another high school assignment my foolish young self found tedious.

Why return to writers and works one has read before, sometimes more than once, when there will never be time enough in life to read everything we want to read? And why the dead of ages past when the present is awash with writers who represent a dizzying array of cultures, ethnicities, genders, and sexual proclivities? I have no doubt that I would enjoy more than a few of them, as I have enjoyed older contemporaries we have lately lost. Cormac McCarthy, Robert Stone, Jim Harrison, and Larry McMurtry come to mind. Even so, the best of the dead, giants on whose shoulders we stand, speak to us as powerfully as ever. They are no less relevant to our human concerns, passions, and trials, our shared humanity, than authors of today. The lure of voices from past eras remains and with it urge to further an incomplete education.

For about ten or twelve years in the 1990s and early 2000s, I reread one of Dostoevsky’s four major novels each winter, having previously read each more than once dating back to my first encounter with The Brothers Karamazov in 1971, fall semester of my sophomore year, at the suggestion of Dr. Mulvaney after I told him I enjoyed Camus’s The Plague, which had been on a list of optional reading for the introductory philosophy course he taught the previous spring. Each reading was a fresh reading that brought fresh and renewed pleasure. Now reminded that it has been a while since I picked up Dostoevsky, I think maybe it is time again.

Lest anyone get the wrong impression, not all of my reading is hifalutin. Far from it. I devoured science fiction throughout my youth until I fell away from it in college. In dubious maturity I presently run through mystery novels in similar fashion. I typically refer to this as lighter reading, a diversion, but that gives a misleading impression of authors in that genre who are quite accomplished in their own right.

Of summer reading I have lately enjoyed, I pick out not quite at random Death at La Fenice by Donna Leon (a Commissario Brunetti novel set in Venice), A World of Curiosities by Louise Penny (Armand Gamache/Three Pines series), and Bride Price and Forfeit by Barbara Nadel (Inspector Çetin İkmen series set in Istanbul). I would be remiss if I failed to mention and recommend Behind the Scenes at the Museum, a most impressive, really a formidable novel by Kate Atkinson that would be found with general fiction in libraries and bookstores.

A better distinction between the myseries and what might be termed more serious fare is to be had from what Bloom refers to as the Shelleyan Sublime, “an experience that persuaded readers to give up easier pleasures for more difficult pleasures.” This is but one expression of the sublime. In How to Read and Why, Bloom differentiates Shelley’s notion from earlier ones:

“The Sublime,” as a literary notion, originally meant “lofty,” in an Alexandrian treatise on style, supposedly composed by the critic Longinus. Later, in the eighteenth century, the Sublime began to mean a visible loftiness in nature and art alike, with aspects of power, freedom, wildness, intensity, and the possibility of terror.

Edmund Burke gave expression to that eighteenth century conception in A Philosophical Inquiry into the Sublime and the Beautiful:

The passion caused by the great and sublime in nature, when those causes operate most powerfully, is astonishment; and astonishment is that state of the soul, in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror. In this case the mind is so entirely filled with its object, that it cannot entertain any other, nor by consequence reason on that object which employs it. Hence the great power of the sublime, that, far from being produced by them, it anticipates our reasonings, and hurries us on by an irresistible force. Astonishment, as I have said, is the effect of the sublime to the highest degree; the inferior effects are admiration, reverence, and respect…

Stodgy old conservative that he is, a veritable damn elitist, Burke goes on to say, “Among the common sort of people, I never could perceive that painting had much influence on their passions. It is true, that the best sorts of painting, as well as the best sorts of poetry, are not much understood in that sphere.” I would say that the best sorts of poetry and literature more generally can be understood and enjoyed on any number of levels. Shakespeare’s plays are an obvious example.

I am drawn to the notion of deferral of pleasure, giving up the immediacy of lesser pleasures for the promise of greater, harder won pleasures to come. One function of the canon is that it provides a list of writers and books from which a reader might reasonably expect to experience a deferred, greater pleasure. This is not to say that a reader is guaranteed to find that pleasure. Nothing is for everyone. Nor are we obliged to like everything. Here again I turn to Bloom for perspective:

Genius is not always lovable. Wharton, like T. S. Eliot and the shattering Dostoevsky, belongs to that small band of writers I am compelled to admire, but do not like. Celine, whom I find unreadable, is a different phenomenon: he is in my garbage bin, with Wyndham Lewis and all but a few fragments of Ezra Pound. Eliot’s hallucinatory poetry and Dostoevsky’s great nihilists, Svidrigalov and Stavrogin, impose themselves upon any authentic reader. Wharton, who had an original genius for representing changing social realities, and for seeing deeply into the war between men and women, is for me a very mixed reading experience. But unpleasant genius is an essential part of what forms the genius of language.

Ability to discern and willingness to acknowledge the significance and worth of works and writers one does not like may be vanishing qualities in our period of cultural dissonance and strife. They bear keeping in mind as we aim for integrity as critics and authenticity as readers of books and poems that make our lives richer than they were before.

Keep the faith. Stand with Ukraine. yr obdt svt