Greetings from the Far Left Coast, where I have fallen in love with Sigrid Nunez, by which I mean her books What Are You Going Through, The Friend, and Sempre Susan. The affair started when a friend recommended What Are You Going Through, the novel on which Pedro Almodóvar’s film The Room Next Door with Julianne Moore and Tilda Swinton is based. I next read The Friend, recipient of the 2018 National Book Award for Fiction. At present I am nearing the final pages of Sempre Susan, a memoir of Susan Sontag (1933–2004). In all three books Nunez writes about things I care about and relate to. She is funny, acerbic, cynical, caring, thoughtful, insightful, moving, sometimes wrenching. I could go on.

This is not the place for a full-blown review of Sempre Susan. I settle for sharing a few impressions that especially resonate. First, some background.

Nunez worked as an editorial assistant at The New York Review of Books between college and grad school. When Sontag asked the editors to recommend someone to help her with unanswered correspondence accumulated while she was undergoing treatment for breast cancer, they recommended Nunez. This was in the spring of 1976 after she had finished her MFA at Columbia. She soon became friends with Sontag, moved into apartment, and began dating her son, David Rieff.

Sontag came onto my radar in the 1960s or early 1970s as a public intellectual and woman of the left. I suppose I first encountered her through essays and reviews published in major periodicals and journals of the day: The New York Review of Books, Partisan Review, The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, The New Republic, etc.; interviews and articles about her in Rolling Stone and Ramparts; and almost surely mention in Time and Newsweek. Against Interpretation, Styles of Radical Will, and Illness as Metaphor are books that come to mind. She was also a novelist and filmmaker.

I recall associating her with French and European thinkers and critics surfacing about that time. Nunez confirms this by noting Sontag’s admiration for Roland Barthes, one of her greatest literary heroes. She first learned of such writers as John Berger, Walter Benjamin, E. M. Cioran, and Simone Weil from Sontag, who was also a cinéaste after my own heart.

She was besotted (another favorite word) with moviegoing—the way, perhaps, that only someone who never watches television can be. (We know this now: if one size screen doesn’t addict you, another one will.) We went to the movies all the time. Ozu, Kurosawa, Godard, Bresson, Resnais—each of these names is linked in my mind with her own…

Among living American writers, she admired, besides [Elizabeth] Hardwick, Donald Barthelme, William Gass, Leonard Michaels, Grace Paley. But she had no more use for most contemporary American fiction (which, as she lamented, usually fell into either of two superficial categories: passé suburban realism or “Bloomingdale’s nihilism”) than she did for most contemporary American film…

What thrilled her instead was the work of certain Europeans, for example Italo Calvino, Bohumil Hrabal, Peter Handke, Stanislaw Lem. They, along with Latin American writers such as Jorge Luis Borges and Julio Cortázar, were creating far more daring and original work…in contrast to banal contemporary American realism. It was this kind of literature that she thought a writer should aspire to, and that she aspired to, and that she believed would continue to matter.

By temperament outspoken, Sontag did not shy away from controversy. As I read Sempre Susan it occurs to me to wonder how she would fare in today’s intellectual and cultural climate. One can imagine how this might go over at, say, NPR:

She was a feminist, but she was often critical of her feminist sisters and of much of the rhetoric of feminism for being naïve, sentimental, and anti-intellectual. And she could be hostile to those who complained about being underrepresented in the arts or banned from the canon, urgently reminding them that the canon (or art, or genius, or talent, or literature) was not an equal opportunity employer.

Picture the reception that would greet this advice to Nunez as a writer: “Don’t be afraid to steal. I steal from other writers all the time.” “Beware of ghettoization.” “Resist the temptation to think of yourself as a woman writer.” “Resist the temptation to think of yourself as a victim.” I suspect it would be not much different from attacks on Sontag in 1982 after she denounced communism as essentially a variant of fascism following a rally in support of Poland’s Solidary movement. I think here of course of comrades on the left. She would be anathema to the right on a host of other counts.

Nunez received “some outraged responses” when she wrote in an essay that Sontag was not a snob. “Everyone knew that she was a terrible snob!” they screeched. Nunez explains that what she meant was that Sontag was not a “class snob.” She did not care about a person’s origins, family, economic and social status. “She was an elitist.” What mattered was how smart you were.

[I]f you had taste and were intellectually curious, you didn’t even have to be that smart. And if you were gorgeous, you didn’t have to be smart at all. And though she could get quite riled at a bookstore clerk who didn’t recognize her name, it was okay when a New York City Ballet dancer to whom she was introduced said, “And what do you do?” (Susan who?)

Sontag “was a natural mentor…who hated teaching,” which she equated with failure. It was a job “and for her to take any job was humiliating.”

But then, she also found the idea of borrowing a book from the library instead of buying her own copy humiliating. Taking public transportation instead of a cab was deeply humiliating…

Going anywhere with her, as soon as you hit the street, she’d stride immediately to the curb, arm raised [she lived in New York].

Nunez speculates that

at least some of her resistance to teaching might have had to do with her passion for being a student. She had the habits and the aura of a student all her life. She was also, all but physically, always young. People close to her often compared her to a child (her inability to be alone; her undiminishable capacity for wonder; her strong, hero-worshipping side and her need to idolize those she looked up to…). David and I joked that she was our enfant terrible. Once when she was struggling to finish an essay, angry that we weren’t being supportive enough, she said, “If you won’t do it for me, at least you could do it for Western culture.

Susan, she writes, gave her permission to devote herself “to these two vocations—reading and writing—that were so often hard to justify.”

“Pay no attention to these writers who claim you can’t be a serious writer and a voracious reader at the same time.” (Two such writers, I recall, were V. S. Naipaul and Norman Mailer.) After all, what mattered was the life of the mind, and for that life to be lived fully, reading was the necessity.

Because of her Nunez resisted switching from typewriter to word processor. “You want to slow down, not speed up. The last thing you want to do is make writing easier,” Sontag advised. “She was loath as well to make the change from record albums to CDs. She was skeptical of new gadgets and electronic devices. Being low-tech was a source of pride to her.” Another topic for imagination: what Sontag would make of social media and the writer as celebrity entrepreneur circa 2025.

Nunez says she never knew anyone more appreciative of the beautiful in art and in human physical appearance—“‘I’m a beauty freak,’ was something she said all the time”—and yet she never knew anyone less moved by the beauties of nature.

Curiosity was a supreme virtue in her book, and she herself was endlessly curious—but not about the natural world. Though she often spoke admiringly of the view from her apartment, I never knew her to cross the street to go into Riverside Park.”

A trip to California to introduce Nunez to the West Coast meant San Francisco and Berkeley. Sontag was less than enthused by Nunez’s idea to rent a car and drive to Big Sur: “she’d already been to Big Sur, for one thing, and she was not interested in natural scenery, no matter how sublime—not when she could sit hour upon hour at the Pacific Film Archive instead while movie after movie was screened for her.”

Though Sontag read voraciously, a book a day was not too much and she owned thousands of them, and wrote like a fiend when the time came, she considered herself a terrible model in her work habits. “She had no discipline, she said. She could not steel herself to write every day, as everyone knew was best.” Nunez attributes this inability to write every day not to lack of discipline but to “hunger to do many other things besides write. She wanted to travel and go out every night”: dance recitals, opera, movies.

To get herself to work, she had to clear out big chunks of time during which she would do nothing else. She would take Dexadrine and work around the clock, never leaving the apartment, rarely leaving her desk…And though she often said she wished she could work in a less self-destructive way, she believed it was only after going at it full throttle for many hours that your mind really started to click and you’d come up with your best ideas.

She told Nunez that when she was writing the last pages of The Benefactor, she “didn’t eat or sleep or change clothes for days. At the very end I couldn’t even stop to light my cigarettes. I had David stand by and light them for me while I kept typing.” Nunez comments that this would have been in 1962 and David was ten.

Sontag married sociologist and cultural critic Philip Rieff when she was a seventeen-year-old old student at the University of Chicago and he a twenty-eight-year-old instructor. Their son was born two years later. She and Rieff divorced five years after that.

The relationship between Sontag and her son was unconventional (okay, an understatement). She thought of herself as a proud mother and expressed regret that she did not have more children. Yet she said she hoped David thought of her more as a goofy older sister than as a mother and that she thought of him as a brother or best friend. Nunez relates that the only “momish” thing she ever saw Sontag do was snatch his dirty glasses from his face and wash them in the kitchen sink.

David Rieff was living with his mother when Nunez joined the household. Nunez says she was already aware of the “feverish, prurient interest swirling” around the residence at 340 Riverside Drive where David lived with his mother well into adulthood. “Is it true? Have they had sex together…They must have had sex together.” When she moved in, the speculation went into overdrive. “What was going on up there?” She adds parenthetically that “the fact of Susan’s bisexuality was, of course, highly pertinent.” At dinner with an NYU professor with whom David was becoming friends, the professor asked directly if the three of them slept together. “When David said, ‘What?’ he simply repeated the question more slowly, as if to a foreigner or an idiot.”

This “feverish, prurient interest” strikes me as at once absurd and absurdly human. Why would it occur to people to wonder, much less turn curiosity into obsession? Yet people do it. Maybe I am the one who is out of tune. The best take on it may have come from a friend who laughed and said, “Everyone imagines the most outrageous scenarios when in fact what you’ve got is your classic possessive, controlling mother and guilt-ridden son.”

Sontag was hyper and liked to have people around. Nunez writes that she herself was far less social, already carrying “the seeds” of the person she would become: “someone who spends ninety percent of her time alone.” This strikes a deep chord with me, and it occurs to me to wonder what JD Vance might think of a man who finds so much common ground with two women. Doubtless his would be a dim view, with the verdict that I am deficient in masculinity. Of all the things that keep me up at night, this would not be among them.

The remarks and impressions here give at best a taste of this slim, immensely rich volume and its complex, intriguing, almost fascinating subject.* It has been quite a while since I read Susan Sontag. Maybe it is time to look at her again.

Scott Simon, Book Review: 'The Friend' Wins 2018 National Book Award For Fiction, NPR, November 24, 2018

Downward into the muck.

I defer to Charlie Sykes to nutshell my thoughts about Schumer, Senate Democrats, and yesterday’s vote on the continuing resolution to fund the government.

This was, of course, the fight that Democrats wanted. This was the fight they needed. It was also a fight they could not have won.

Chuck Schumer’s decision to cave on the CR was greeted with understandable disappointment and outrage because Democrats finally had a chance to fight. they finally had leverage. They could have at least tried.

But Schumer folded.

And he probably made the right call.

Trust me, folks: emotionally, I wanted this fight…

But…my head tells me it’s a mistake…

In this case, the options were atrocious. The House GOP CR is a partisan mess and an extraordinary surrender of Congressional power (over tariffs) to the president…

But—and I really hate to write this—the alternative was worse, because Trump/Musk would love nothing more than to shut down the government that they are in the process of dismantling. And, as Schumer notes, there was no clear exit from a shutdown…no plausible way to “win.” (Schumer Caves)

Jonathan Capehart offered a spirited counterargument yesterday on the PBS News Hour. David Brooks countered Capehart’s counter (Brooks and Capehart on the Democratic division over the stopgap funding bill). I have thought long and hard and waffled greatly on this. A shutdown would likely have made it easier, not more difficult, for Trump and Musk to escalate their rampage. At the end I come down uneasily with Brooks and Sykes.

It was cheering to read that JD Vance was heartily booed and jeered when he and Usha Vance took their seats Thursday evening for a National Symphony Orchestra concert at the Kennedy Center. Perhaps lady Vance was checking it out in an exercise of due diligence as a new Kennedy Center board member. Otherwise JD’s attendance is puzzling. This is a man who in a 2016 interview with The New York Times expressed astonishment upon learning “that people listened to classical music for pleasure” (Charlotte Higgins, Andrew Roth, ‘Ruined this place’: chorus of boos against JD Vance at Washington concert, The Guardian, March 14, 2025). Maybe he saw his presence as a thumb in the eye of the elite.

For those interested, new reports related to issues taken up in Wednesday’s piece The Disappearing of Mahmoud Khalil:

Anna Betts, Pro-Israel group says it has ‘deportation list’ and has sent ‘thousands’ of names to Trump officials, The Guardian, March 14, 2025

Nick Miroff, There Was a Second Name on Rubio’s Target List, The Atlantic, March 14, 2025

Amna Nawaz, Trump administration targets college and university budgets in DEI crackdown, PBS News Hour, March 14, 2025. With video of Mahmoud Khalil’s arrest.

Danny Nguyen, Education Department launches investigation into dozens of colleges, Politico, March 14, 2025

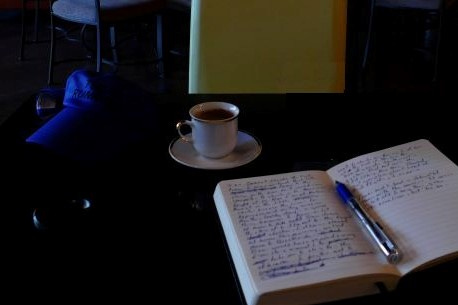

There is more, always so much more. Moments ago while taking a break before final review and revision of this newsletter, I spotted a report about a new round cuts that will include the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in the Smithsonian Institution and the Institute of Museum and Library Services, which funds grants to libraries and museums across the country (Ali Bianco, Trump’s next agency cuts include US-backed global media, library and museum grants, Politico, March 15, 2025). As a friend commented, “we have to keep processing these acts somehow to not numb out.” We also have to, as a favorite cap from Powell’s Books puts it, “Fight Evil Read Books.” And watch films. And expose ourselves to art.

Keep the faith. Stand with Ukraine. yr obdt svt

*Memo from the editorial desk March 16 6:16 a.m.: I wrote in precipitous haste. In the last paragraph of the section about Sempre Susan, “slim, immensely rich volume and its complex, intriguing, almost fascinating subject” has been substituted for “slim and immensely rich volume” at the end of the first sentence.